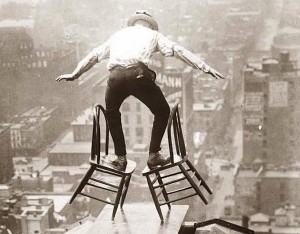

Never Risk Your Whole Business on One Show

By David A. Barber

Author of Gigging, Everything You Need to Know About Playing Gigs (Except How to Play Your Axe)

Never Risk Your Whole Business on One Show

This one is more for promoters/venues/ booking people than musicians, but sometimes a band will want to put on their own show or a musician might want to venture into the world of concert promoters, so read it anyway.

We’ve seen this happen too many times. A new, inexperienced or stupid person puts on a huge show, loses their shirt and ends up bankrupt, out of business and generally worse off than they were beforehand. The music business can be very risky. A snowstorm (or hurricane or another weather event) can ruin your show. Bands can get stuck in another state (geographically…) or get sick and cancel at the last minute. The cops or fire department can shut you down without warning. All sorts of unexpected things can and do happen in this business. You need to be prepared for the worst and make sure that whatever show/event you’re planning isn’t going to ruin you personally, bankrupt your business or land you in court, jail or worse.

If you’ve come up with a clever way to exploit an apparent loophole in the liquor laws that would allow you to serve beer after hours, you should probably check out your idea with the authorities beforehand (an anonymous phone call from a payphone asking about the laws, in general, can do the trick without giving them enough info to track you down) Most city and state governments want new businesses to succeed (and pay taxes) so if there’s a way to do it legally, they might even help you get the right permits, etc. Or, if there’s a law/ordinance you weren’t aware of, they’ll tell you right upfront, before you waste a lot of time and money or worse before you get arrested.

A well-planned event/concert should be profitable or close to it before you even open the doors the night of the show. Advance ticket sales, sponsorships, booth rentals, etc. should add up to cover your expenses and if they don’t, if they aren’t even close, or if it snows two feet the day of the show, just cancel it. Many debts will not have to be paid if the show does not go on (some will – like the deposit you made on that huge national act) but anything you can cancel far enough in advance to prevent the vendor/band from showing up, will not need to be paid. If the beer vendor doesn’t sell any beer, you probably owe him nothing.

If you have no experience with putting together a multi-day, multi-stage festival, don’t do it. Start small. Book some shows into local venues with local acts first. Get your feet wet and learn from experience. Put on a one-day festival with one stage and make a profit before you expand to three days and six stages. It just makes sense.

Here are some true stories of people who bet it all on one show and blew it, big time.

There was a monthly music magazine called Riff. It was doing well and turning a small profit. To celebrate their anniversary of two years they decided to throw a huge Halloween event. They rounded up a bunch of volunteers, secured a venue and booked a bunch of bands. The venue was one of those huge entertainment complexes with a video game arcade, bowling and tons of other stuff. They set up several stages and scheduled local bands to play all evening and into the night. We watched this all happening and noted that not one of the people involved had ever even helped out with an event of this magnitude before. When we heard that they’d booked a big national act (an 80s metal band) it looked to us like a recipe for disaster. We were right. Stories started filtering out the next morning. There had been a guest list of hundreds of people (all the bands and volunteers were allowed to put people on the list) hardly anyone who attended had paid. Certainly, not enough tickets were sold to offset the costs of the event. There was a story about a brand new, big, flat-screen TV being damaged by one of the punk bands in the green room. The venue wanted $5.000 to pay for the damage. But worst was yet to come: The woman who was in charge of the event and who had booked the national act went on record stating that the band had asked for cocaine and she supplied it as if that was a standard professional thing to do. Needless to say, she got arrested at the event and had serious legal problems to deal with. With all this bad press and unwanted expenses, the magazine went under, never to publish again.

This story goes back to the late 1980s. A hotshot young promoter arrived in Denver with the goal of establishing a concert promotions business. He claimed to have been working for a big concert promotions company based in New York. Anyway, he set up a concert here. The headliner was not a big name that everyone would recognize, instead, it was the lead guitar player for a big name band. The show was to be an all day outdoor event. After the first choice venues became unavailable (or simply turned the guy down, realizing the show would flop), the show was scheduled for the soccer fields at Auraria Campus. A nice location, but one where alcohol was prohibited. Then, he booked his opening acts. He unwisely consulted with a local booking company, who promptly got him to book a load of local acts with the promise that each one would bring in 500 people. This raised a huge red flag in our minds. We were familiar with these local acts and knew that they commonly played shows with two or three of them on the same bill in rooms that could hold 250-300 people. Those shows generally had cover charges around $5. This big concert had a $15 ticket price. We ran into this would-be promoter the night before his big show and he generously provided us with comp tickets. We asked how the ticket sales were going and responded that they weren’t selling very well and then he dashed off to the airport to pick up his headliner. Needless to say, the show was a monumental flop. Our estimates at the time were that this guy had lost as much as $50,000 for his company (maybe less, since the half dozen local acts never got paid) and this promoter and his company were never heard from again in Denver. His mistakes were many: Bad venue, with no alcohol sales, a headliner who wasn’t big enough, unfamiliarity with the local scene, which resulted in him actually believing the local bands would bring in 500 people each. (At $15 a head, on a Sunday, with no beer) We had a good laugh when it started raining in the middle of the whole event and the several dozen people who did buy tickets cleared out pronto. It’s still funny from our perspective, but we wouldn’t want to have been in that promoter’s shoes.

Here’s a much more recent story: A small downtown venue had been working hard and booking a variety of acts for a couple of years. They had become profitable and were building a strong reputation in town when the owner was offered a large sum of money to sell the place. He took the money and never looked back. The new owners didn’t have much if any, experience with running a music venue, though, they did own other bars/restaurants. They remodeled the place to make it look really swanky. Initially, they kept the booking the same, with very successful Sunday and Monday night punk and metal nights. After one guy put up a band sticker in the newly remodeled men’s room, they canceled those nights. But their big mistake was New Year’s Eve. They booked A national touring act and started selling tickets for $100 apiece (which included a nice dinner). Needless to say, the show flopped and the place was vacant within a month. They bet the whole business on one show and lost.

Here’s a story we were actually involved in. A few years back we set up a non-profit, tax-exempt organization with the goal of throwing concerts and donating the proceeds to charity. We were approached by a guy who showed up at every meeting wearing his long-expired Great White backstage pass on a lanyard around his neck. He was an accountant by profession with zero music business experience, but a strong desire to be a big-time concert promoter. He showed us this big fat binder which supposedly contained his business plan for putting on a huge Bonnaroo-style music festival. We should have walked away and never returned his calls, but instead, we decided to go with the flow and see how things developed before bailing out. Over the course of a month or two, his plans scaled down to a two-day concert event at a local county fairgrounds. In Colorado, you can’t sell liquor on a publicly owned property unless it’s for a non-profit (who are also required to obtain the liquor sales license and do the actual sales). Now we were on the hook and a couple of our board members had gotten even deeper involved, becoming the de-facto production managers. Of course, the plans for booking went awry and the show ended up being one afternoon and evening of country acts and a day of locals and has-beens with the headliner being… you guessed it, Great White. Knowing this was likely to be a disaster we did everything we could to salvage the show, including arrange for media sponsors, and make sure the beer distributors were going to show up with beer. The country show flopped and everything was riding on the second day. Attendees were supposed to purchase tickets and then redeem those for beer/food. When the tickets ran out, we started accepting cash. We knew the whole affair was likely to end badly, in a financial sense, so we took in every penny we could for our charity. Some of the other vendors weren’t quite so lucky. Towards the end of the show, the accountant’s brother, who made a critical loan beforehand, raided the box office to make sure he got his loan back and then split. The headliner got paid cash at the end of the night and there really wasn’t much left after that. Not only did our charity get stiffed, but so did all the other vendors, the staging company, the sound crew, the security staff, the beer distributor and the local bands. Mr. accountant with the fancy business plan, disappeared as soon as the legal threats started flying, and we, proactively, made certain no beer distributor in the state would ever go near him again. Not only did this guy put himself out of business, but he also damaged a variety of other small businesses and stiffed a charity. Never work with a wannabe concert promoter.

This one may be the most interesting. A group of local musicians rented out a large warehouse/factory space in an industrial part of town where they lived, recorded, and rehearsed. Eventually, they also threw a party. Realizing there was some potential for income they made a bold move. They started throwing after-hours parties with bands. In order to skirt the liquor laws, they charged a cover at the door but gave away the drinks (at least until the keg ran dry). They threw these parties once a month for maybe a year, using the proceeds to pay their rent. Having played almost every club in town, they advertised by simple word of mouth and had really huge numbers in the door. Mostly bar/club/restaurant employees looking for something to do after closing time. Unfortunately, they hadn’t found an actual loophole in the liquor laws, turns out the laws are clear that even charging a cover counts as selling liquor and when the parties got too big and neighbors complained, the cops found out and shut them down. Unfortunately, it was so serious that the organizers got hauled off to jail and eventually court, where big fines were applied. The point of this story: Always make sure what you’re doing is legal, before you get busted.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post